How We Actually Get Stronger

Strength is arguably one of the most important physical qualities that we can possess in terms of overall health and longevity. Yet it can be an elusive subject for a large majority people who pursue it.

On one end we have the typical fitness trainee who thinks of their strength as a measure of their physical competency, being the manifestation of their ego. This is the mindset (which is more common than we like to admit) that leads us to believe that our strength needs to be maximally displayed at all times (unfortunately, displaying our maximum strength all the time can lead to serious injury, fatigue and lack of long term progress). On the other end, we have the person who never wants to exert themselves because they are either in fear of sustaining an injury or simply don’t have the appropriate belief systems to see the value in what they are doing [See our article on why motivation & Laziness are red herrings and a lack of belief in value is the true culprit behind a lack of exercise]. In both of these cases, the person in question has some very misleading perspectives on strength, what it actually means for them, the benefits of pursuing it and how to best go about doing so!

And this is a real problem. Because muscular strength is something that is critical to our lives. The intelligent pursuit of it can be somewhat of a fountain of youth and one of the main things we can all do to give ourselves the best chance of a life of good health.

We most commonly hear this term being thrown around by well-meaning people who have heard that muscular strength is a good thing. This could be a physician, surgeon or rehab provider that has told the person that ‘getting stronger’ will provide them with improvements to their condition, pain and function. While this is true, it is unfortunately not always that simple and so today we want to provide you with some of the basic physiology behind strength and then go into the best ways to sustain and build it.

How to use this Article Series

- This is the summary of 4 years of undergraduate study in human physiology, so it will take some time to fully digest.

- Think of it as the schema to hang all of your knowledge of human physical performance on, whether it be athletic endeavours, our ability to get out of pain, or simply how we adapt to the environment around us. It will help to explain what separates elite athletes from the average everyday person, the potential each of us has within our own body, why we get injured, the most likely causes of injury and pain as well as a heap of other highly relevant topics.

-

We suggest that you use this article as a reference guide to cross-check anything that you read in the future.

-

Think of this resource like a comprehensive guide that is incredibly well-referenced, with pre-eminent articles from both the research and from the field.

-

The best way to get an understanding is to skim through the articles at first. We have provided a nice summary at the bottom of each article in order for you to quickly understand the context of the material. We want for you to first become aware of the concepts, by reading what we have written then constantly refer back to the article and the materials linked within it to pique your interest over time. Should you have any questions about any of it, we will be available to answer them for you.

-

We have purposefully written this article in a manner that makes it directly relevant to the reader. We have designed the whole article to be able to give context about the story of human performance, without going into too much detail. While going through this story we have provided reliable links to important resources that we know and trust so that you can delve into information that has been well-curated, should you want more detail and context. This series has around 50+ independent articles linked within it, which is a mass of information. We would not suggest reading this all at once. Use the articles like an encyclopedia, saving them somewhere easy to access so that you can readily access the information when you need it.

So, what actually is strength?

Physical (Muscular) Strength: An animals ability to exert force on an object.

Force is our measure of muscular strength. Typically strength is talked about without factoring in acceleration (which is a factor in muscular power)

Muscular strength is often thought of as one of the most admirable physical qualities anybody can possess. A large part of this is the fact that our society holds strength up as a virtue with the noblest connotations of heroism and courage being associated with the word. For the purposes of our discussion today, let’s separate the way most people think of strength from a mental and emotional standpoint to (typically thought of as our ability to pursue a difficult endeavour) from the physical quality of muscular strength. This will allow us to separate our use of the term ‘strength’ from the positive mythological connotations that are often associated with it.

To break down the component parts of strength nice and simple, I have enlisted the help of Muscular Physiologist, Dr Andy Galpin to explain the Physiology of Strength in 5 minutes. Dr Galpin breaks it down into 3, simple component parts, which I have adapted for our purposes.

-

-

- Neural component or CNS (i.e. Mobility, Force production, lack of inhibition, balance, coordination etc.)

- Muscle contractile component (i.e. Morphological changes e.g. fibre hypertrophy, calcium sensitivity, fibre type transformation)

- Connective tissue component (i.e. Tendon Strength, Collaginous matrix, Tendon Stiffness & force absorption + elasticity, bone density)

-

These components give us our first look at seeing what goes into muscular strength. You can find out more about the specifics by clicking on the associated links within the above text.

Now we want to give you some practical information to set you on the right path in your understanding and pursuit of strength (see a brief history of modern strength understanding for more detail on the science).

It’s Not All Or Nothing [Frequency & the importance of sub max strength]

How does this apply to your life?

When training it’s important to work consistently & frequently. This is the same for the person who has severe knee pain & struggles to get out of the chair, as it is the elite CrossFitter. The key is to intelligently ‘train’ at the right sub max intensities to elicit a given result.

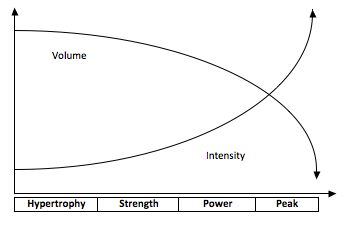

The importance of long term ‘periodisation’ when it comes to training. Periodisation is simply a fancy way to describe planning. The reason why it’s called periodisation is because it involves breaking a period of extended training (anywhere from a few months to multiple decades) into a series of component parts that focuses on particular qualities in each part. Because the human system is a series of chemical reactions occurring constantly (Lets say a rough estimation of 37000000000000000000 per second) that contribute to the functioning of a whole host of independent systems that all leads to our ability to function in certain tasks (this example uses sport as the task), things can get quite complex. There are a lot of independent systems that contribute to our ability to perform in sporting endeavours (i.e. Muscles, Nervous system, Skeleton, Connective tissue, Cardiovascular, Gene expression, pancreas and hormonal function), each of which will adapt differently to different kinds of training stimuli. What we know from years of studying sporting performance is that the body responds to these stimuli in a fairly predictable manner (i.e. The specific demand that is placed upon the body will lead to a specific adaptation in response to that demand). The principle that underlies this response is known as the SAID principle. What this principle shows is that that human system as a whole will respond to a specific set of stimuli in a specific manner to impose a specific adaptation on the host of independent systems that are involved in responding to that stimuli. In other words, when we practice we get better.

But here’s the catch.

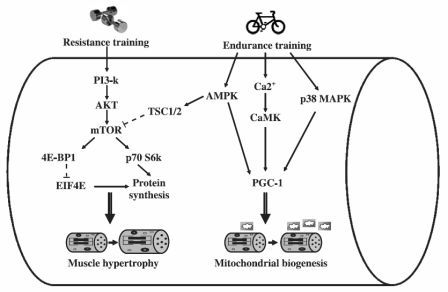

There are certain rules that govern our ability to adapt to the demands our body faces. In fact, certain physiological qualities will compete for the valuable adaptive resources our body has. One example of this is the cell signalling pathway for endurance (AMPK) when compared with muscular hypertrophy (mTOR). This classic review shows how the biochemical signalling process related to the synthesis of mitochondria (the energy-producing components of a cell related to endurance) can actually have a blocking effect on protein synthesis (the creation of muscle). This serves as a perfect example of one of the chemical reactions that govern our ability to adapt and the interference that training for two different qualities at the same time can have on it (other examples are the competing demands of maximal strength VS maximal Power VS maximal speed, body fat % VS physiological performance, Strength VS Skill, Maximum strength VS Maximum muscle size). Sadly, there isn’t sufficient research to document a lot of these competing adaptations, however, coaches have anecdotally known these things for years. That is why they came up with the theory of periodisation, so they could take into account the overarching goals of the person they are working with and apply basic physiological principles to best manage the training of that person over the length of their entire training career.

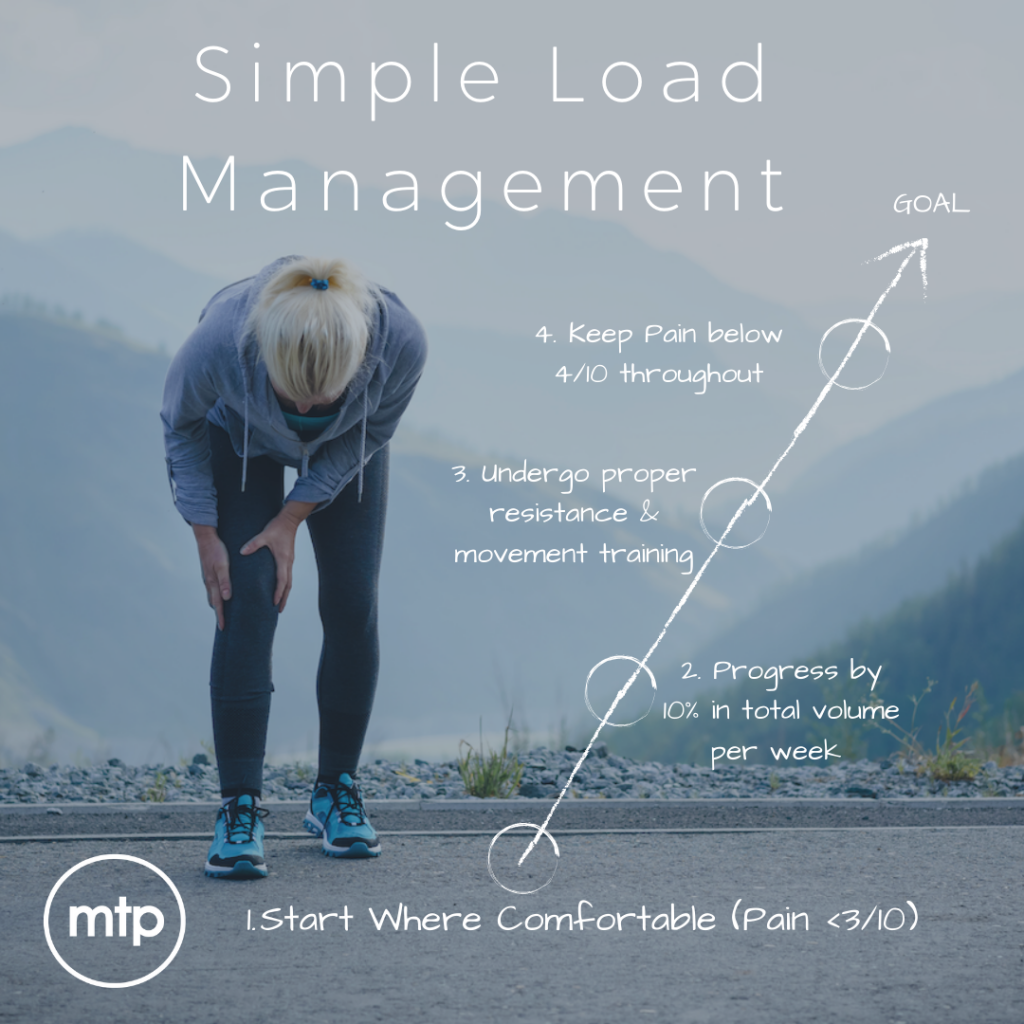

This same concept applies to you. Whether it’s your physical training, sporting or your rehab, intelligent planning is a must to help you get the most out of what you’re doing. For most people, the best form of periodisation they can apply TODAY to reach their goals is a simple load management chart [See our Guide to calculating loads here], along with using the principles of movement hierarchy. Sadly, this is something that is seldom done, which is why so many people never achieve their physique, performance or rehab goals.

A Universal Guide to Simple Load Management in Any Activity

Another example of competing training demands ties back into the first example we have of the person who’s ego is attached to their physical strength. They feel the need to maximally exert themselves at every opportunity and think in an all or nothing manner. If they aren’t able to outperform everyone else in the room, then they feel like they would be better not coming at all. This is a flawed mindset that can lead to two major things happening. Firstly they will almost definitely underperform over the long term, as they will very likely not be able to respect the focus it requires to properly periodise in their training and focus on what they need to do now to achieve their long term goals. This most commonly plays out in the max strength VS max size tradeoff. If this person is aiming for maximum muscular size, then the most important thing is their overall training volume. What we would see if they tried to show off their strength at every opportunity they got would be an increase in their overall fatigue and thus training quality decreasing over time. Eventually, this would put them at much greater risk of injury and underecovery as their body simply wouldn’t be able to adapt to the intense stimulus it faced [See More On Optimal Training Volumes]. On top of this, because their ego is getting in the way of their ability to intelligently train, they are much more likely to become discouraged with their training and give up entirely. You can see how this quickly becomes a zero-sum game. Training is not black and white. Doing something is always better than nothing.

When Volume Goes Up Intensity Has to Go Down. This is Why We Cannot Exert Our Maximal Strength 100% of The Time

To further hammer this point home, I want to showcase the example of Andy Bolton, the man who deadlifted 1000 pounds for the first time & didn’t go over 800 pounds in his 8 weeks of training beforehand. That’s how fatiguing truly intense strength training can be. What allowed him to perform such a crazy feat of strength, was lots and lots of intelligently planned (circa 30 years of training that respected the human body’s physiological adaptations), frequent practice at submaximal intensities (between 30-80% of his max). If we jump back into our present reality & apply this example to ourselves, we are left with the golden rule of training to create an adaptation: consistency (or volume as Strength training calls it) always wins. Any step towards achieving your movement goal is better than nothing. It takes stimulus to cause an adaptation to our body. The more frequent and habitual that stimulus becomes the more likely the body will adapt.

When Considering Strength It’s Incredibly Important To Address the Components That You’re Lacking Within The Movement Hierarchy Before Going All Out On Strength

Common Misleading Perspectives on Strength

Strength training is bad for my back [Insert another joint]

Strength Training is for macho guys who are too vain to care about anything else

Strength training isn’t that good for my health

Strength training will stunt my growth

The benefits of pursuing Strength

The list is extensive, but here’s the summary: It’s amazing.

- Systematic review improved all Health-Related Quality of Life measures.

- Anecdotally Strength training seems to be the most cost-effective and time-efficient way to optimise someone’s health. It makes sense. We evolved lifting things. Our body was designed to be exerted and adapt. Without doing this, our system begins to maladapt and fail.

- Strength underpins just a large majority of physiological adaptations that improve someones ability to perform.

- Research has shown benefits to specific things like Mood, pain management, prevention of chronic disease, prevention of cognitive decline, positive weight management, lower body fat, more muscle mass, improved sense of well being & confidence. This is just a brief summary.

What Does Strength Actually Mean For You?

Why are you wanting to strength train? Do you want to look good? Did your doctor tell you to do it? Is it for your X condition? Do you want to be able to do a certain activity?

The question of why is fundamentally critical to designing an effective strength training program. Often people confuse muscular size with strength [See our article on CNS to understand why this is a problem]. Similarly, many people see strength training as their sure-fire way to get fit, strong and better at anything they wish. This is also an oversimplification. While strength training certainly has a litany of benefits, it can also be specifically applied to create different types of benefits that could be more suited towards a certain goal. E.g. Does the person simply need as much muscular strength as possible or do they want muscular size? Or do they need to perform at a given activity as best as they can? All of these 3 goals involve 3 quite different training protocols.

How to Best Go About Building It

We’ll try to make this as simple as possible.

Without touching on all of the different goals we spoke about above, there are some things that work. Here is our shortlist

- Plan your training for the long term (at least 1 year). Think about how long you plan to train for. It should ideally be as long as you are alive. What do you want to be able to do as a result of your training? This is how you start.

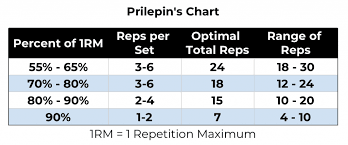

- Use 55-90% of your max when training (See Prilipens chart below for a great starting guide). NB: The example of Andy Bolton listed above features %’s that are adjusted to someone with an incredibly high training. This means that he has spent years optimising his bodies capacity to handle high loads, while teaching his nervous system to disable it’s safety mechanisms that regulate force production (i.e. his body his minimal regulations). This means that he is able to use lower %’s that still stimulate massive adaptations as his body is incredibly efficient at producing force. A human frame is still a human frame and so 400+ kgs will cause fatigue no matter who it is.

- If you’re serious about it, see a professional. Physiological change is pretty damn complex if you hadn’t realised already. That’s why people spend at least 4 years in specialised university programs to learn how to most effectively elicit these changes in the human body. There are thousands of factors that need to be accounted for and if one of these is not properly factored in, it could result in suboptimal performance, fatigue and or serious injury.

Quite possibly the greatest simplification of how to create physiological adaptations to improve Muscular Strength

Ok, I Get it Strength is Complex, But What Do I Do With All This Information?

The Bottom line is this: Strength is a complex phenomenon that is extremely beneficial for human health when pursued intelligently.

In this article, we wanted to showcase how we can go about pursuing it intelligently. We have broken down the rough physiology of strength and hopefully, shed some light on what goes into it. We then went on to talk about some of the misleading perspectives many people have on strength and what this means for them. Littered throughout this article are pragmatic ways to more appropriately implement strength training into your life, as well as why it is so important. Here are a few key takeaway points:

- You will learn to love it (everyone should be doing it): The benefits of strength training are too vast for you not to enjoy it once you start to see progress. This is because of our inbuilt reward mechanisms that are perfectly set up to find physical exertion in the form of resistance training highly addictive.

- Plan for the long term: the key to achieving absolutely anything is finding something you want to achieve & creating an effective, clear plan that fits with your lifestyle in order to achieve that thing. Strength training is something that everyone should be doing and should suit your life accordingly.

- Take all factors into account: The human body is incredibly complex. Only when as many factors as possible are taken into account, can we come up with a program that will produce the ideal result that we desire.

- Something is infinitely better than nothing: Don’t think on an all or nothing scale. Work at your own level, respect your place on the movement hierarchy & load management continuum and progress appropriately.

- Doing it often is your best bet for success: The king of all adaptations is frequency. Think of exercise like a drug. It needs to be taken often enough and in the right dose to create the response you desire (find a professional who can tell you what this dosage is if you’re unsure). The best way to think about approaching strength training is to think as if you’re going to be doing it for the rest of your life. So take your time, build into it slowly and set yourself some goals that will constantly build upon each other.

Other Parts of this series

- Part 1.1 – The The Neuromuscular component [A Body With No Limits]

- Part 1.2 – The Neuromuscular component [Movement Hierachy]

- Part 2 – The Muscular Component [Physcial, contractile Muscle]

- Part 3 [Coming SOON] – The Connective Tissue Component [The Forgotten Child]

Links

- The Effect of resistance training on health-related quality of life in older adults

- How does training volume affect muscle growth

- Is there an optimal training volume per session

- The basics of Hypertrophy Training

- Research Review on the interference effect of training

- Basic practical introduction to periodisation

- Optimal recovery time for strength & power gains

- Andy Bolton and the Story of 1000 pounds [everything that goes into superhuman performance] – this is a great example of intelligently planned training that anyone can take a lesson from

- Resistance training, a scientific evolution of our understanding – a detailed look at the scientific study of strength over the years.

- What is Strength – Showcasing the difficulty in defining strength, due to the vague nature of the term and the many ways in which our body can exert strength.