What Actually Causes Osteoarthritis [Part 5: Abnormal Joint Loading]

Abnormal joint loading. The name implies that there must be such a thing as ‘normal joint loading’ right? Well, to some extent, this would be correct. However, we want to make it clear, that we are using the term ‘abnormal joint loading’ for a specific purpose. As such, the term has been expanded on, compared to its usual definition.

Firstly, let’s define abnormal joint loading for our context.

Abnormal joint loading: force applied to a joint of the body that causes a maladaptive response, leading to pathology.

What does this mean? Essentially, it means that the factor that contributes to Osteoarthritis (OA) in the context of abnormal joint loading is that force is being applied in a way that further causes the OA to worsen. This is where the idea of ‘wear & tear’ came from.

In some circumstances, exercise and physical activity past a certain level or at too high of an intensity can absolutely cause the progression and onset of OA. In fact, this is commonly why a lot of recreational athletes begin to develop OA. But as always there is a lot more going on under the hood than we might think.

Firstly we must remember that the human body is an adaptive organism, constantly undergoing a process of adaptation to the stimuli it faces. That’s why physical activity can be so good for us. It forces our body to grow stronger and adapt to a stimulus it is designed for. However, when we try to do too much, too quickly and don’t respect our bodies current capacity and need for recovery, then we can encounter problems.

And that’s why this is the area where we at MTP health find that we are able to create the most change. It’s because it’s incredibly hard to get right. It requires a comprehensive understanding of human physiology from a university qualified professional in order to properly account for all of the factors involved. This is the crux of musculoskeletal medicine and a big part of what makes MTP Health so unique.

So what are the factors that can contribute to ‘abnormal joint loading’?

- Acute or chronic overload

- Muscle weakness/ imbalance

- Altered gait

- Injury [See part 2]

Acute & Chronic workload

The concept of acute & chronic workload was popularised by Tim Gabbett, back in 2015. It was also known as training stress balance in the past and is essentially the same concept.

It is an explanation of a fairly simple concept. Our body needs time to adapt to high workloads and if we spend time outside of those workloads (either too high or too low), we run the risk of injury. What that means for the person who is at risk of knee pain is that if they rush into doing too much activity, too quickly, they run the risk of making their issues worst. However, on the flip side, if they spend too much time doing nothing, they run the risk of their body becoming accustomed to this, meaning that they are more likely to get injured during their daily activities or when they might need to kick things up a gear (the classic weekend warrior injury syndrome). We touched on this concept in this post about the real story of osteoarthritis.

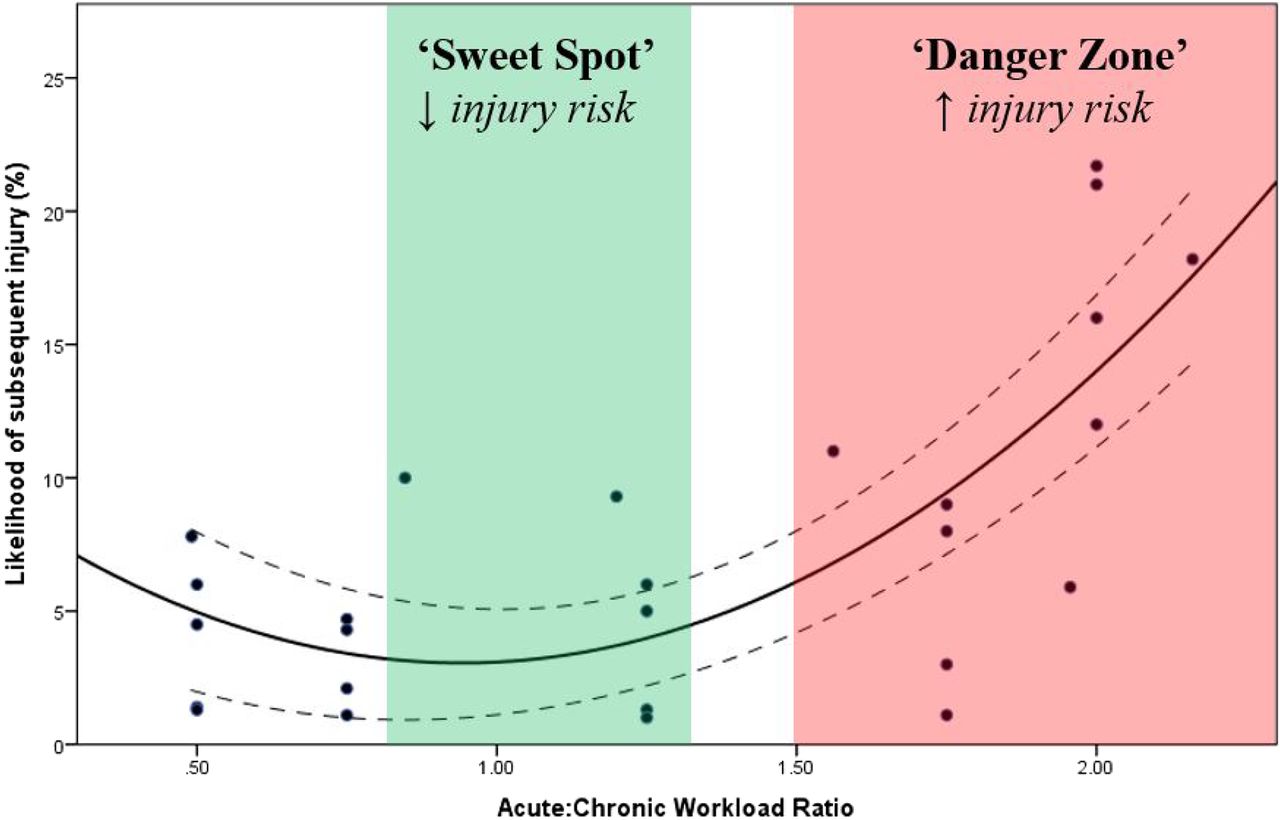

Acute:Chronic Workload Ratio & Injury risk [Gabbett 2015]

To further illustrate this concept, we will run through a couple of examples.

In the first example, we have a middle-aged former runner, who decides they want to get back into running. They used to be really active when they were younger, running hours each and every day. They were part of a running club and managed to run in a couple of half marathons here and there. They were always a pretty good athlete and never really experienced any series injury, apart from the odd ‘tweak’ here and there. Now, it’s been 5 years since they last did any running. Since they had their kids, things became really hectic and so exercise went to the bottom of the priority list. That coupled with a hectic schedule at work and physical activity all but vanished. As a result that have put on about 7kgs (which is around 12% of total body weight). Because they used to run so often, they figured that it won’t be a problem to get back into things. They’ll just start out light and ‘ease’ back into things. So they start running, deciding that they are going to make a commitment to themselves, I’ll just something every single day, doing a little more each day. Within 2 months they’re pounding the pavement up to 10km per day and pushing it to the max each time. They notice a little bit of pain but decide that it’s probably nothing, so they keep pushing through it. 6 months later, the pain has gotten worse and they have only managed to lose 3kgs. They are happy with their progress, however, decide that they should probably go and see a physio. After seeing the physio, they ask for an X-ray. After getting the X-ray, the physio bears the bad news. They’ve got OA. And look how bad it is! The physio advises an immediate cessation of running, prescribing some ‘strengthening exercises’ immediately. They go through the exercises and see the physio repeatedly over the next few months. They notice improvements in their pain, but don’t feel like they’re really making that much progress. Things are great when they’re in the clinic, but when they are at home, they can’t quite seem to do them right. After a few more months of this and frustration at their absolute lack of progress, they decide to go and see a specialist. They are sent to a sports doctor and then off to a surgeon. The surgeon advises they are too young for surgery and that their pain isn’t severe enough. He tells them to do some exercise and lose some weight. They think to themselves: “That’s how this whole thing started!”.

If this example above sounds pretty normal to you, chances are, that’s because it is! It’s probably also got you thinking, damn, why would I bother with exercise then!

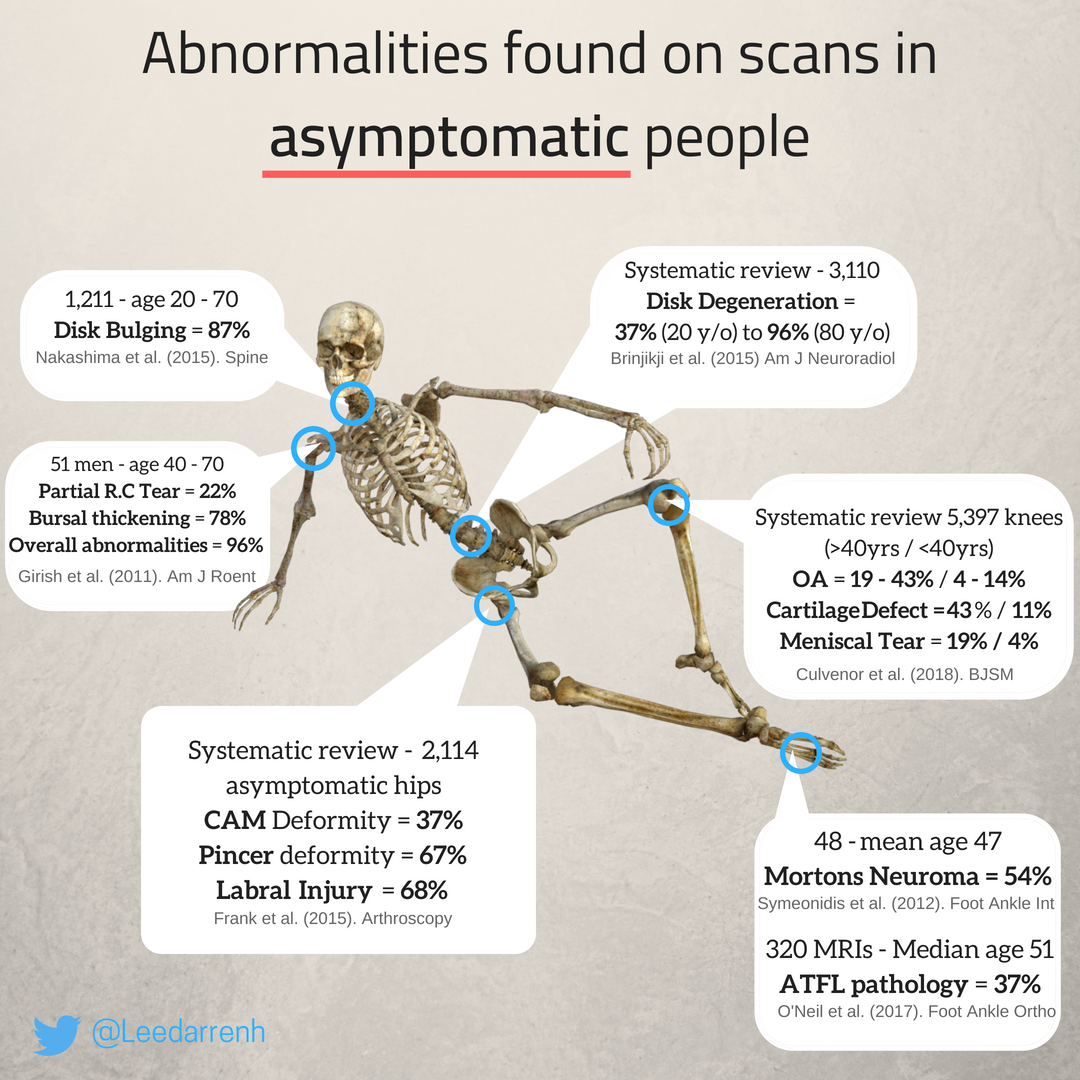

It also perfectly highlights the concept of acute: chronic workload in action. What has happened in this example is the person in question has not respected their body’s recovery time when undergoing their new running regime. They have jumped straight back into things at an intensity their body simply wasn’t ready for (with a ratio of over 4.0 in some weeks; well over the 20% increase in injury likelihood shown in the graph). As such, they began to experience small amounts of degenerative changes in their joints, along with an increased pain response. And yet the interesting thing about all of this is that these degenerative changes may have already been present. In fact, just because degenerative changes occurred, doesn’t necessarily mean that it was a bad thing. Recent evidence has shown that x-rays are an imprecise guide to predicting if arthritis is likely to have a functional effect on someone’s life. Just because arthritic change is present, doesn’t actually mean that pain will be present at all!

X-Ray / MRI is doesn’t predict pain – The % of people who experience no symptoms with structural changes in various joints

The most difficult thing about the acute: chronic workload ratio is that it can be incredibly hard for the layperson to define. Unfortunately, pain is not a reliable indicator of how much load the body can tolerate (as shown above). As a result, it’s all too common for people to do far too much and end up seriously hurting themselves in the process. The same holds for people that do too little!

The key is to be like goldilocks, use precise tools of measurement and expertise to pick a level that’s not too high and not too low. We want an intensity that’s just right!

Muscle Weakness/ Imbalance

The next factor that we consider when we look at what contributes to abnormal joint loading is that of muscle weakness and or imbalance.

Working with this aspect of chronic musculoskeletal conditions is our bread and butter and is in fact where MTP started from. Move Train Perform (as MTP stands for) is our motto of how we progress the people we work with from pain to function. The idea is that by improving the areas of weakness and or imbalance, we are able to address the issues that are causing their problems in the first place.

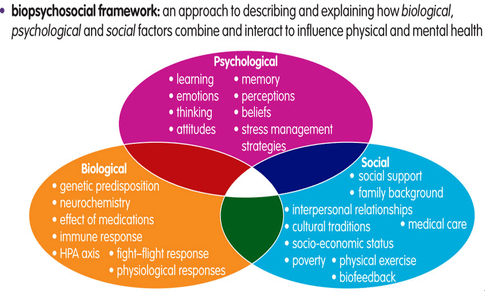

Now, with that said there is currently a lot of debate amongst professionals as to how important the ‘corrective’ component of exercise is. Popular notions such as structural changes to the tissue being the cause of pain relief have prevailed for a long time. The idea was that our body is like a machine. ‘Fix’ the broken parts and you fix the machine. However, recent research is showing that isn’t quite how things work. It seems to be a whole lot more complex than that. What actually seems to occur is some interplay of all of the elements involved in the biopsychosocial model of pain, with our perception of our own capability and resilience being a huge factor in the way we experience our condition.

The Biopsychosocial Model and the factors that contribute to pain Pain

However, regardless of what actually leads to the pain, we know from our own personal experience that when we correct common movement imbalances and muscle weakness, such as lateral hip control (strengthening the glute medius to prevent knee valgus). While the evidence isn’t quite conclusive, from an anecdotal point of view we certainly see a huge benefit in this type of therapeutic exercise. We would consider this the neuromuscular component of our programs, which then leads into our resilience-building phase. All of this is achieved while concurrently getting the benefits of resistance based training.

Altered Gait

The third factor that contributes to abnormal joint loading is altered gait.

This is as much about the perception of injury, as it as about the physical injury itself. Our general take on altered gait is that it should be avoided at all costs, the longer we adjust our movement outside of our normal patterns, the more chance we have for maladaptation to occur.

That’s not to say that people who walk with an altered gait have it solely in their heads. There are a lot of factors that may lead to someone altering their gait. Most commonly it’s either:

- Perception of injury or threat of damage

- A change in muscular loading due to weakness from injury (only likely in patients with injuries that require altered movement for > 6 weeks)

As soon as it is safe to do so, we want to return someone to the activities they were doing before they were injured. That way we can ensure their body is able to function properly and continue to respond to the loading stimuli of their daily and recreational activities. It’s the use it or lose it principle in action!

The perception of threat is best highlighted in someone who has rolled their ankle. If you have ever experienced spraining an ankle, you will remember how difficult and painful it can be to walk. Chances are they physio would’ve encouraged walking as soon as possible (provided the injury wasn’t too series). Those first few steps were likely incredibly difficult and painful. The brain had to recognise that the ankle wasn’t broken and the injury sustained wasn’t too serious. As soon as you gave your body the chance to move as normal again, the pain would likely have subsided massively as they were able to walk normally again. If you continued limping around, or even worse, casted your foot, you would’ve opened the door up for more serious injury down the line, as your body would have to re-adapt to the activity levels you were at during the time of injury.

To further illustrate the last 2 factors of gait and muscle weakness, let’s use another example. This time we will give her a name. Wendy has started to experience knee pain. She went to see her doctor immediately, just to make sure that nothing was seriously wrong. Her doctor advised her to take pain killers and continue on. Wendy, being more conscientious than most people, requested that she get an X-Ray to make sure nothing was wrong. Her doctor, not wanting to get in an argument with her in the short time they had together, reluctantly obliged. When Wendys X-ray came back, the doctor gave her the bad news. You’ve got arthritis and looks to me it’s almost bone on bone. When she asked how this had happened the doctors said, “it’s just wear and tear, a normal part of ageing”. Since then Wendy was extra careful. She began to notice more and more pain and started leaning on the handrail when going upstairs. She stopped going for her nightly runs and began to walk less and less. Her physio gave her some basic strengthening exercises and advised her to rest as the pain dictated. For Wendy, this meant basically every day. With all the activity Wendy was no longer doing, she began to notice she was gaining weight. In 6 months she gained 5kgs, which was nearly 10% of her bodyweight. The longer she went on, the weaker she felt and the worse her pain got. Then when she went skiing to her favourite mountain 2 years on, things went seriously wrong. She felt a twinge and her pain got significantly worse. The specialists told her that nothing was wrong, but she was sure something was. After the injury she underwent comprehensive scans and MRI’s, all indicating that her OA had worsened, with no other damage. This continued to worry her as she didn’t like the thought of putting any other unnecessary pressure on her knees. Now she walks permanently with a limp and cringes at the thought of stairs. She struggles with activity and has really limited her movement throughout the day.

This is yet another all too common example of someone who has begun to suffer from arthritis, much more than is necessary as a result of the unhelpful narratives that prevail in our healthcare system. It all stems from the belief of the patient that the body is like a machine that will ‘wear out’ over time. This belief can be further exacerbated and worsened through unnecessary medical imaging that further highlights abnormality. As we outlined previously, the damage is a normal part of ageing. Just because abnormality is present, doesn’t mean that pain or function will be adversely affected. What the example above really highlights is a person who is suffering from the negative effects of the biopsychosocial model of pain. More specifically, the belief that their body is fragile and susceptible to damage as a result of their normal activity, coupled with the focus on the pain during daily living creates a negative environment for pain to persist. We will touch on this idea more in part 7, however to get a clearer understanding of why this pain may be occurring we recommend this video. In our experience, if we can get Wendy to believe that all she needs is to start to use her body as she once did and begin to build her back up we can get amazing results in regard to her pain and quality of life.

Injury

As we touched on in part 2, injury is one of the biggest contributors to causing OA. The mechanism is a result of an initial disruption to the cartilaginous matrix, when then over time leads OA developing. However as you will remember, there is still a lot that can be done about it. The biggest thing we need to remember when we have sustained an injury is that we are far more likely to develop OA in the long term, however, we can mitigate this through a healthy lifestyle, being aware of things that may put us at risk.

Conclusion

So there you have it.

The blueprint of what we do best at MTP.

By addressing the top 3 factors of: Workload, Muscule Weakness & Altered Gait, we provide the people we see with the best chance at getting themselves towards an optimal level of function. We find that when we address these things and educate people on the rest, we provide their body with the absolute best chance of healing itself.

It’s all about ‘Improving The Way People Move’ so we can empower them to live their best lives. And that’s how we know that we’re able to deliver musculoskeletal medicine that is of world-leading quality.

References

- What is Abnormal Joint Loading

- The training—injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?

- The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature.

- Do structural changes (eg, collagen/matrix) explain the response to therapeutic exercises in tendinopathy: a systematic review

- Abnormal joint loading and the association with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

- TEDxAdelaide – Lorimer Moseley – Why Things Hurt