What Actually Causes Osteoarthritis [Part 6: Genetics]

Those who are healthiest and most active are also the least likely to develop Osteoarthritis

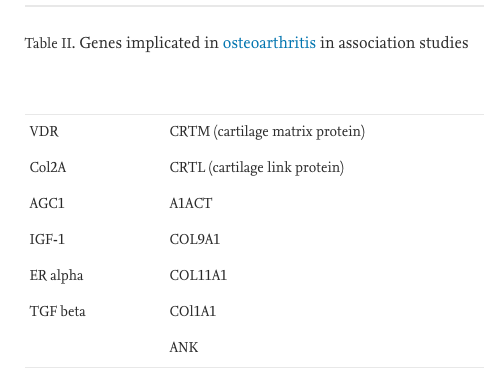

Specific Genes

[Spector & McGregor 2003 – Risk factors for osteoarthritis: genetics]

Sex

We know from research that there are significant sex differences in the prevalence of Osteoarthritis, with females being more likely to experience adverse quality of life and negative radiographic imaging when compared to males. A number of theories have been proposed as to why this is the case [see some here]. Once again, like everyone else in the prior parts of this series, we don’t exactly know why this is the case. We certainly have theories and can guess, however, we can’t pinpoint it down to the exact factors.

When looking at this factor from our perspective, we like to provide the facts, while also addressing the things that we can work with. One of these factors is improving the lateral hip control of the people we work with. This is a huge contributor to knee pain, as when the hip lacks control, it causes the knee to go into what is known as a valgus position. This position leads to excess stress on the medial compartment of the knee, which can cause abnormal joint loading (as outlined in part 5). In females, this valgus position tends to be more exaggerated due to differences in anatomy. The factor that causes this increased valgus is known as the Q-angle. The theory is that the wider the Q angle, the more likely an individual is to sustain an injury (such as a ligament tear), which can lead to the development of OA (as outlined in part 2).

Q Angle Differences in Males and Females. A large Q angle, will expose a knee joint to more stress during daily activities.

Biomechanical factors

This factor is essentially encompassed within what we talked about in part 5, as well as the example described above. It is, however, worth discussing as a standalone point as it can be a significant contributor to OA. This article highlights what affects misaligned biomechanics and abnormal loading can have on a joint. It essentially describes the physiological processes that take place when abnormal loading takes place (as described in part 5). It doesn’t delineate whether or not these biomechanical factors are related to genetics or lifestyle factors. However, for our purposes, this does not matter, as a number of genetic factors can be stimulated by environmental stimuli (i.e. lifestyle).

What we want to focus on here is that our genetics can pre-dispose us to certain biomechanical positions that pre-dispose us to OA. This can be things like increased knee valgus as a result of an increased Q-angle (as shown above), as well as other things such as propensity to over-pronate at the feet. There is a large number of factors that can have an effect in regard to skeletal anatomy. The same holds true for the muscular system. Some people will be more likely to have less muscle mass. This means that in the long run, they may be at a greater risk of developing osteoarthritis through the lack of ability to control their body. The same holds true for those who are ‘hypermobile’. They will be more likely to sustain ligament injuries, which in the long run could lead to the development of OA.

Despite all of this, the key to addressing all of this is properly prescribed exercise. Exercise that addresses all of the factors that may be likely to cause problems down the line and gears to person up to not only manage those issues, but make sure they never even become a problem.

Conclusion

In sum, we see that genetics can indeed have a big impact on the risk of us developing OA in our lifetime. This does not mean that it’s a full gone conclusion. There are tonnes of things that can be done to mitigate the risks of developing OA (which have been outlined in this article series at length) including diet, physical activity, specialised exercise and a healthy lifestyle. All that knowing someone’s specific genetic makeup will do is help them to identify how careful they need to be and how much action they need to take.

But our message is this: why wait? Why not just start living a healthy lifestyle and doing all of the things you have always wanted to do from a physical activity standpoint?

Evidence has shown that this is the key to making sure OA never becomes a problem. If you already have OA, then it’s your best bet to manage your condition and live the happiest and healthiest life possible.

The problem that most people have when they try to do this is that they don’t know where to start. And that’s where we come in. All of our programs are designed with the specific goals of the person in front of us in mind. Whether they have Osteoarthritis or not, we work with them and the issues that they have to provide them with the best possible exercise program for them and give them the best chance at living an empowered life.

The Role of Genes in Osteoarthritis [Spector & McGregor 2003 – Risk factors for osteoarthritis: genetics]